Interior of transformer room, predecessor to Western Colorado Power Company, which later operated this facility.

Interior of transformer room, predecessor to Western Colorado Power Company, which later operated this facility.

Later, Western Colorado Power, and later the successive mining and milling corporations.

Later, Western Colorado Power, and later the successive mining and milling corporations.

By William R Jones

The Animas Power & Water Company

1906 Powerhouse Sub-Station

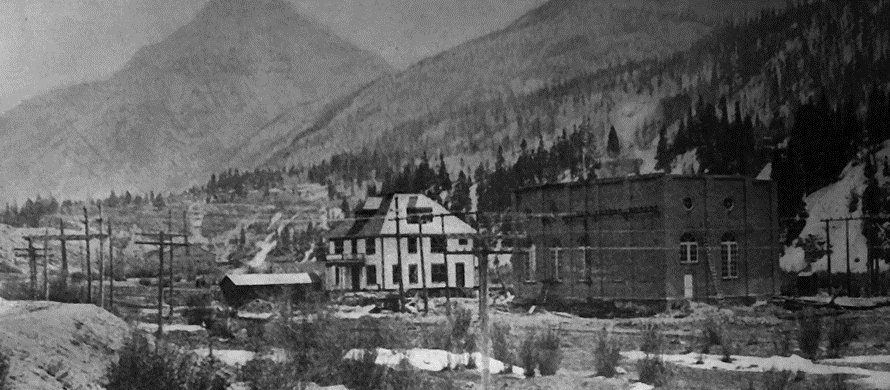

About a mile east of Silverton stands an imposing brick structure along the Animas River known locally as the "Powerhouse". Completed in 1906 this 40 foot wide by 50 foot long 30 foot tall building was once the "brain" of the area's pioneer electric power grid. Although electric power came early to the mines, (Nickola Tesla's radical new alternating current system was first demonstrated at a mine in Telluride), each mine had to generate their own power. This was usually done with large stationary steam engines turning the generators, though some used water power. But steam comes from boilers, and boilers depend on coal, and coal depends on the railroads to haul it up the narrow canyons to the mines and mills. It was expensive, and winter avalanches often blocked the trains and when the coal ran out the mines shut down. Something more reliable and lower cost was needed.

San Juan mining was rapidly expanding in the early 20th century and eastern capitalists took note. Mines needed power and would be a lucrative captive market. A group out of Indianapolis and New York, no doubt seeing the success of Tesla's 1895 hydroelectric plant at Niagara Falls, came up with their own audacious plan to build a single AC electric power system linking all the mines in the San Juans, including those in Ouray, Telluride and Silverton. A century before the concept of "green energy" was common, the new Animas Power and Water Company would not burn a pound of coal to generate electricity, it would be done with water: hydro-electric power. A new "golden" age was dawning in the San Juans, and on September 27th, 1907 the Silverton Miner published its lavishly illustrated "Golden San Juan Edition", whose first major article touted the... "new energy that is spreading out over the San Juans".

The Juice That Makes the Wheels Go 'Round

The waters of the mountains have been harnessed... to generate the electric current that is sent sizzling back for forty miles over glittering bands of copper to the headwaters of the streams... to move the wheels that create the juice which fiercely flows along the wires though canons and over mountain top to many mines, where men have sought to reclaim the wealth from rock-bound vaults among the hills that God built."

While local papers were well known to exaggerate, in the case of the Animas Power project, the hyperbole was justified - the modern age of electricity had reached the San Juans, and Silverton was right in the center of it! Over a century later, much of the (now modernized) Animas Power and Water system still serves as a part of San Miguel Power Association, even though the mines it was intended for, are but a distant memory.

The heart of the AP&W system was the generating station at Rockwood, along the line of the D&RG narrow gauge railroad. Here, water from the Electra Lake Reservoir drops 1,000 feet to the power plant's two 3,000 horsepower General Electric pelton type turbines. Built at a cost of $1,300,000, the plant and initial power line to Silverton delivered its first power on April 15, 1906 sending it to the Gold King Mine at Gladstone. But the 50,000 volt power used for the 25 mile transmission line to Silverton was too high to be used directly by the mines. It must first be "stepped down" to a lower more workable voltage using transformers to make 17,500 volts for the transmission lines to the mine sites. To do this, a sub-station enclosed in a transformer house was needed to act as the central distribution system.

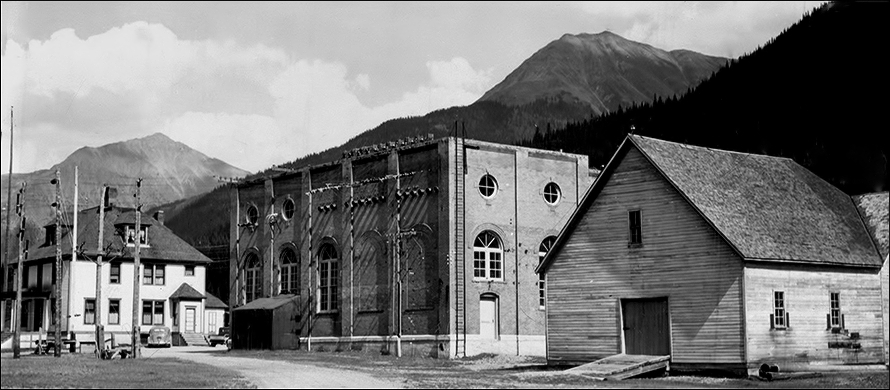

Like the center of a giant spider web made of copper wires, the Silverton sub-station was the brains of the AP&W system. Here the 50,000 volt power line from Rockwood terminated. Its wires precisely entering the top of the massive brick structure centered through the round holes in the high brick wall to prevent catastrophic arcing of the high voltage to the ground. Inside, three massive water cooled General Electric transformers lowered the voltage. Multiple "low-voltage" wires then weaved their way out the opposite side of the building through ceramic insulating tubes, to connect the feeder lines strung up the canyons and over the passes to Gladstone, Eureka, Animas Forks, Red Mountain, Camp Bird, Ophir, etc. Existing company systems at Silver Lake and Sunnyside were connected to the new "grid" which offered reliable power at half the price of the inefficient company systems. Nearly every mine now had access to cheap reliable year-round power to run the new air compressors that ran the new air drills, new aerial trams, and new ball mills and stamps - all ran on electricity now. It was indeed an industrial revolution ranking right up with the introduction of the steam pumping engine in Cornish tin mines 150 years prior.

Later part of the larger Western Colorado Power Company, Silverton's "Powerhouse" remained an integral part of the local network through decades of boom and bust. Adjacent to the sub-station, a frame office building and living quarters were built for the local manager. In the days before 4-wheel drive trucks, electricians used mules and mule trains to build and repair the rugged high altitude lines so a mule barn was built. In the 1930's the powerhouse even had its own narrow gauge "galloping goose" - an open top flatbed rail car made from a Pierce Arrow automobile for traveling up and down the narrow gauge tracks to service the power line to the Rockwood generating plant which was only accessible by rail. The distribution system in the Powerhouse controlled the power to all the distant mine sites.

But by the late 1950's automated substations were built which did not need a building or full time staff. The old transformers were scrapped and Silverton's Powerhouse became obsolete. In 1960, the site was sold to the new Standard Metals Corporation who was reopening the Sunnyside Mine in Gladstone and the Mayflower Mill, just up the road from the old power complex. The office was used by the mining company while the now empty Powerhouse and mule barn became a warehouse. A truck scale was added to the side of the building and the power company's timber shop was used to make mine timbers. An assay office was even built in one of the back rooms of the structure (where the author went to work in 1977).

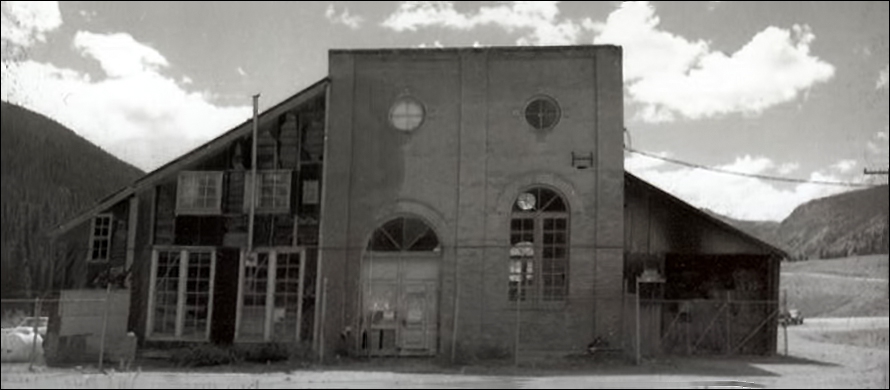

In 1988, the mine's new operator Sunnyside Gold Corporation moved its offices to the former County Hospital. The old AP&W office building was donated to the town and was moved to the entrance to Silverton to become the Visitor's Center. When the Sunnyside Mine closed in 1991, the Powerhouse, now rapidly deteriorating, was abandoned. The roof leaked and the brick walls were literally falling apart in some sections. In 1996 Sunnyside Gold donated the buildings and the land to the Society for preservation and re-used. But what to do with such a massive brick building needing expensive repairs?

The solution lay in combining historic preservation and economic development. With the mine's closure, Silverton's economy was in a tailspin. With unemployment over 17%, Federal Economic Development Administration (EDA) funds were available for developing a business and industrial park to help the local economy. These funds could be used as match for a Colorado State Historic Fund grant to restore the historic Powerhouse building. In this way over $900,000 in grants were secured for the project. In 2001 the project started and a new water distribution system and pipeline that tied the Powerhouse to the Society's Mayflower Mill water system was built. Lots with utilities were developed and subdivided for sale to new and existing businesses. The street where the Silverton Northern Railroad once ran was named Mears Avenue in honor of the pioneer road and railroad builder, Otto Mears. The street in front of the Powerhouse was named Mathews Street in honor of Hammond Mathews, the innovative manager of the Powerhouse in the 1930's and 40's who kept the increasingly antiquated system running through depression and war.

Using the Colorado State Historical Funds, the historic Powerhouse building was painstakingly restored brick by brick by local contractor Klinke & Lew who later bought a lot and built a new building to house their businesses. The main Powerhouse building is now home to Scotty Bob's Custom Skis. Other local businesses thrive at the Powerhouse Business Park.

The Society's Powerhouse Project is a model for how historic preservation can help a community take what was once an abandoned crumbling eyesore, turning it into a useful building generating the revenue that is the key to its long term preservation.