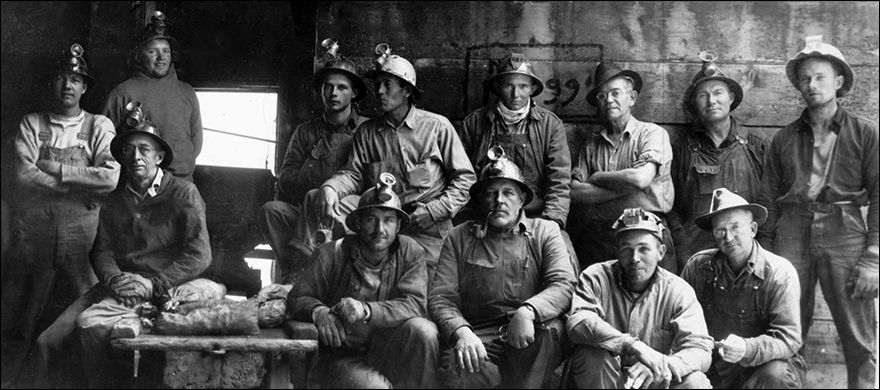

Last Crew to Live at Old Hundred Level #7 Boarding House

Last Crew to Live at Old Hundred Level #7 Boarding House

By Ray Dileo

By Ray Dileo

Plaque Was Set by Lisa Richardson, BLM

Plaque Was Set by Lisa Richardson, BLM

Please help us MAINTAIN the Old Hundred Boarding House with a DONATION to the San Juan County Historical Society.

By Scott Fetchenhier

The Old Hundred Mine: It Devoured Millions

"A mine is a hole in the ground with a liar for an owner" ~ Mark Twain

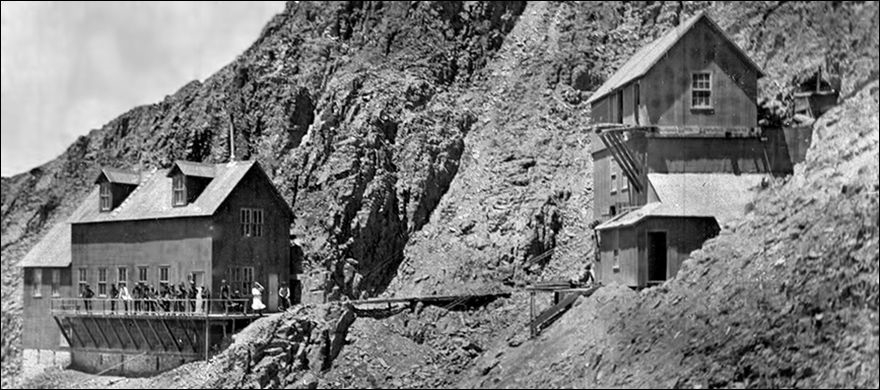

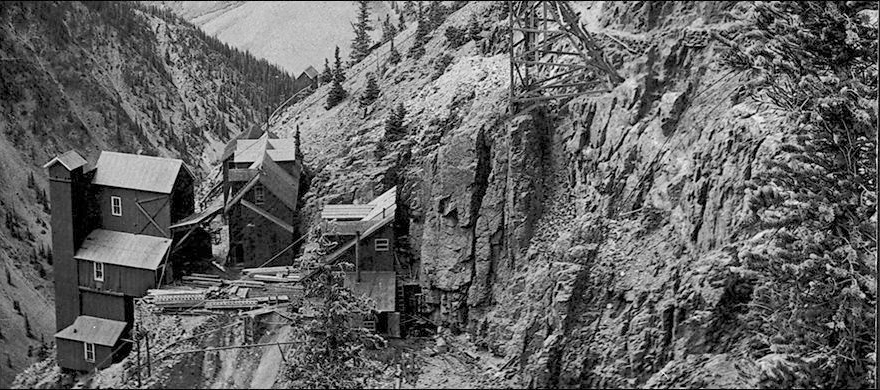

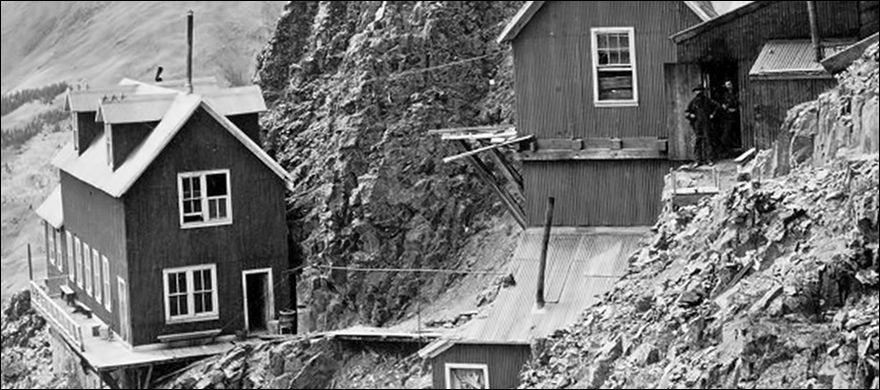

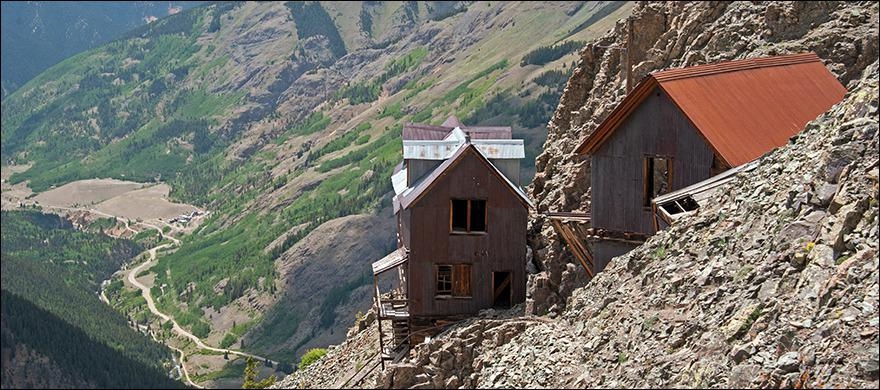

One look at the Old Hundred Mine bunkhouse and tramhouse nestled high amongst the rocky crags of Galena Mountain conjures up visions of tough, hardened men bound and determined to wrest from the mountain its golden treasures. Men risking their lives to blast trails and tunnels on shear mountain sides, hauling thousands of feet of cable up precipitous slopes and living precariously above the valley floor.

Romantic visions of fabulous veins, laden with gold, of fortunes made overnight like those made by the Stoibers, millionaire mining tycoons of Silver Lake fame, flash through the imagination.

Unfortunately, if one had the misfortune to have been an investor in the Old Hundred Mine these visions rapidly faded as the mine devoured millions of dollars while thousands of feet of barren vein were uncovered. Stockholders despaired as the veins, consisting mostly of quartz, paid little in return, let alone dividends.

There are two large veins running southeast to northwest on the steep sides of Galena Mountain. The lower or more westerly vein is called the Old Hundred, Niegold, or #5 vein, while the upper or more easterly vein seen outcropped above the Old Hundred tramhouse is the #7, O. Roedel, Hawkeye, or Veta Madre vein.

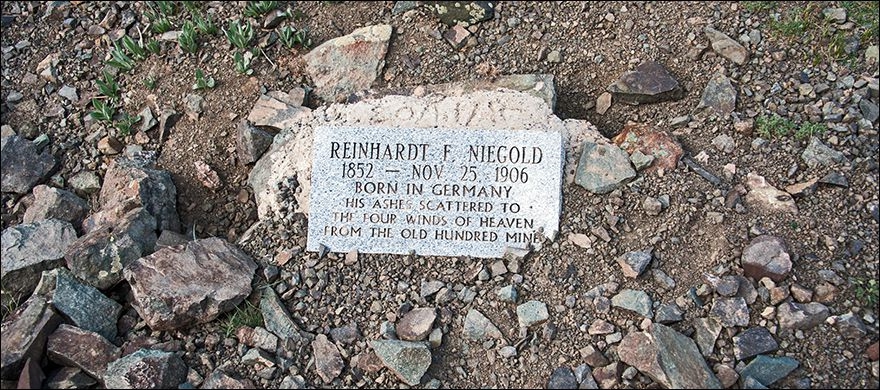

Reinhard Niegold was one of the earliest prospectors to find the veins on Galena Mountain. Niegold was in the area as early as 1873 and probably built a cabin at this time at the beginning of Stony Pass. (A. Nossaman, Many More Mountains). No mention of the properties is made until January 28, 1882 when the Midland Mining Company, made up of Reinhard Niegold, his brother Gustave, half brother Oscar Roedel, and their friend Clarence Colburn file claim on the #5 and #7 veins. The R. Niegold and Augustus Begole claims were filed on the #5 vein while the O. Roedel claim was filed on the #7 vein. The Old Hundred claim, filed on the northern extension of the #5 vein was filed later than the R. Niegold claim at its southeastern edge.

The Niegolds, originally from Saxony, Germany were an interesting and talented family; Reinhard was an accomplished pianist while Gustave was an opera singer who had sung professionally in New York. The brothers performed the latest operas for their friends and neighbors appearing in "knickerbocker pants, powdered wigs, and buckle shoes" as related by Freda Peterson in her Hillside Cemetery book. Reinhard played on a grand piano brought over Stony Pass by wagon. The brothers were known for their "propensity for good food, wine, and Turkish tobacco" (Hillside Cemetery book). Many a traveler or prospector probably broke their long and lonely wanderings with a stop at Niegoldstown at the base of Stony Pass.

The Niegolds worked their properties and prospected on Galena Mountain through the early 1900's. They ran almost one hundred feet of drift on the Old Hundred vein in the early 1880's and worked a seam of silver bearing galena while shipping sorted ore by pack train. The brothers were most likely the only owners of the Old Hundred to have made any money on the properties. The Midland Mining Company eventually lease-optioned their interests to the newly formed Old Hundred Mining Company in 1904.

The Old Hundred Mining Company was organized in 1904 with much hoopla and fanfare. It was supposedly financed by Cyrus Davis and Henry Soule, two Boston investor who eventually bought the Gold King mine. Howell Hinds, a Cleveland promoter was the driving force that put the initial package together. The company began an impressive program of development in the fall of 1904, building roads, trails, trams and a 125 ton per day mill built by the American Bridge Company at a cost of $450,000 dollars.

The trail perched precariously above the Old Hundred tramhouse and winding back to Stony Pass was built at the cost of $32,000 dollars. A forty man bunkhouse and cabins for twenty men were built at the bottom of Cunningham Gulch while tramhouses and bunkhouses were built far above at both #5 and #7 levels.

Three tramways were built to the various levels of the mine-the first, a 1850 ft. long Bleichart tram was built from the lowest terminal at the mill to the #2 level and was only 650 ft. long. A second Bleichart jig back tram, using the loaded weight of a single ore bucket to pull up the empty bucket on the other side rose 520 ft. between #2 and #5 levels. With an angle of 48 degrees the ride up was a breathtaking rise that left at least on newspaperman clinging to the sides of the ore bucket. The third tram, built high above the gulch between #5 and #7 levels rose 1200 ft. and was 1700 ft. long.

One can picture grumbling miners, bundled up in their long johns with blankets on their laps, riding the swaying buckets to work in the howling storms of winter. A cold, wet miner, riding the trams back and forth from work was also susceptible sickness and the ever present danger of pneumonia. A least two men working for the mine died of pneumonia in the winters of 1905-1907. Many miner's lungs, already weakened from the dread disease of silicosis were easy targets for pneumonia.

Drilling and blasting began in early 1905 as crosscuts were driven to intercept the #5 and #7 veins. Over 15,000 ft. of drifts and raises were driven between 1905 and 1908. Newspaper reports were glowing as they lavished praise and compared the Old Hundred mine to some of the area's larger mines such as the Sunnyside. By 1907, Manager Davis was preparing to order more mill machinery to bring the mill up to an 800-1000 ton per day capacity. The new mill level tunnel was in over 800 ft. and a connecting shaft between #2 and #5 levels was begun.

This flurry of activity came to an unexplained stop in August of 1908 as any further mention of the Old Hundred disappears. Actually, the ceasing of mining operations came as no surprise- 114,388 tons of ore were milled for a value of $480,000 dollars. Approximately one million dollars was spent on trams, buildings, milling, and mining for a negative return of a half a million dollars (ten million smackers in present day banking circles). Of the $500,000 spent on actual mining operations $275,000 disappeared through "promotions and deep pockets". (Mishler 1931).

The property reverted back to the Midland Mining Company and was idle until 1927 when Carl Dresser from Bradford, Pa purchased the Gary Owen and the Old Hundred mine from the Midland Mining Company for $400,000. Dresser's dream was to open up the Old Hundred property with money made from ores mined at the Gary Owen mine. The unfortunate Dresser ended up selling most of the stock that he owned in his father's company, the Dresser Coupling Company to finance the mining venture. The Gary Owen was mined for three years until the fall of lead prices and the untimely death of Dresser in February of 1930 put a screeching halt to mining operations at the mine and the preparatory development of the Old Hundred.

At this time Benjamin Webster came into the picture. Webster, a mining engineer, had come to Silverton at Dresser's request in 1928 to manage the mining operations for a salary and percentage of the property. In 1934 Webster managed to convince W.G Roeder and Frank Calkins, a Pennsylvania banker, who were representing Mrs. Dresser, that they were to good to sell. (Webster needed a job and some way to keep his interest in the mine).

In 1934 Webster managed to convince W.G Roeder and Frank Calkins, a Pennsylvania banker, who were representing Mrs. Dresser, that they were to good to sell. (Webster needed a job and some way to keep his interest in the mine).

Webster and Roeder called on poor Charles Kimball from Sisterville, West Virginia in 1934. Kimball, with their advice organized a group of investors in 1935 to form the Old Hundred Gold Mining Company and bought out Mrs. Dresser. The tram to #2 level was revamped, the flotation mill refurbished with new equipment and mining operations begun. Over 90 men were employed in January, 1936 with most of the mining concentrated on several levels of the #5 vein. Webster mentioned that all of the stopes on #7 level were filled with ice and that severe weather and avalanches hampered much of the work through the winter. The eastern investors dabbles in the mining industry lasted from November, 1935 to March 1936 with a loss of

Webster, who still owned a share of the property, continued to promote the mine for many years. He ignored a negative report by consulting geologist J.H. Rodgers in 1940 that said, "further development of these properties, the Old Hundred, the #5, Gary Owen, and Sterling is not, in my opinion, an attractive mining venture". This was not the first negative geologic report on the property- R.T. Mishler said much the same thing in 1931 but no one seemed to have read his report. In fact, another group of investors in the early 1970's and a mining company in the early 1980's most have not read any of the reports either.

The name of the Old Hundred was not mentioned again until 1947 when the Old Hundred Gold Mining Company began mining operations at the Gary Owen mine, again hoping to use the proceeds to begin operations at the Old Hundred mine. B.F. Webster was mine and mill manager until the summer of 1951 when William Sandell took over mine operations and Webster the mill. Superintendent Sandell had some disagreements about manager Webster's handling of milling operations as evidenced by Sandell's letter to Kimball in 1952. "The mill had no labor. The only three good pieces of equipment area a ball mill, filter, cone crusher — the rest is junk. Your $20,000 was spent in high cost, inefficient labor. The mill hasn't been hit in an avalanche in 60 years though a mudslide damaged the side of the mill several years ago."

Apparently, the mill barely ran for a few hours after its "extensive renovation". The operation at the Gary Owen mine and the Old Hundred mill stopped sometime in the summer of 1952. The Old Hundred was sold to the United Mining Corporation sometime between 1952 and 1968. They sold the property to the Dixilyn Mining Corporation (Webster must have done on heck of a lot of promoting!).

Dixilyn Mining, an oil company from Texas, came into the San Juans in 1968 and left without it in 1972. Dixilyn decided to "wildcat" the property but turned up with a "dry hole". Because of encouraging results the company spent millions of dollars on a mechanic's shop, compressor room, dryroom, engineer's and geologist's offices, assay lab and hired 75 employees.

Dixilyn decided to "wildcat" the property but turned up with a "dry hole". Because of encouraging results the company spent millions of dollars on a mechanic's shop, compressor room, dryroom, engineer's and geologist's offices, assay lab and hired 75 employees.

Dixilyn had other properties in the area but most of these were about as productive as the Old Hundred. They poured several million dollars into the operation while producing some of the most expensive gravel ever mined in San Juan County. Dixilyn shut down its mine in 1972-1973, but amazingly enough, the Old Hundred wasn't finished yet.

Asamera Minerals came into the area looking for a gold property in 1981 but made a wrong turn at Cunningham Gulch instead of heading for the Sunnyside mine. Asamera began an extensive drilling program in the dead of winter. The drilling program lasted for several months as local cat skinners struggled to keep the steep road to the #2 level and the Gary Owen mine plowed as avalanches swept the area daily. Asamera wisely decided to pull out in the spring of 1982 — they to left a substantial deposit at the Old Hundred.

The rusted and weather tram and bunkhouse at Seven level can still be seen high upon the slopes of Galena Mountain. In the early 1980's the bunkhouse still had the long dining room tables that weary miners ate at after a long shift, while the kitchen still had shelves on the wall, a stove and large chopping block table in its middle. Upstairs on the second floor were twenty five wooden bunks, many with graffitti from another era carved into them. One room behind the tramhouse was blasted into solid rock and curiously, contains a steam radiator. Though one local artist thought it was used as a sauna, it was most likely used as a powder magazine and heated to keep the dynamite from freezing.

The bunkhouse had steadily collapsed over time, weather and marmots take their toll. All that remained of the massive Old Hundred mill is its concrete foundations, much of which was covered up by Dixilyn's operations. The large concrete portal at the lowest tunnel collapsed sometime in 1989.

We are proud to announce that the San Juan County Historical Society has been awarded $48,750 by the State Historical Fund to work on foundation repairs to the Old 100 Boardinghouse. This is matched by $13,000 raised from folks all over the country who are as in awe of the building as we are here in San Juan County. The Colorado Department of Reclamation, Mining and Safety is also donating the helicopter time to lift supplies and tools to the site. The construction firm of Klinke and Lew will do the work. Klinke and Lew were the contractors that performed the stabilization work on the Boarding House in 1998.

RESTORATION, 1998: The Old Hundred Boarding House was about to disintegrate. Two-thirds of the roof was caved in due to years of heavy snow and neglect. But, thanks to the cooperative efforts of the Old Hundred Mining Company, the San Juan County Historical Society, the State Historical Society of Colorado, the Colorado Division of Minerals and Geology, the BLM, and some REALLY GUTSY carpenters (and helicopter pilot!), the building was saved for several more years.

November 2014 UPDATE: The Old Hundred Boarding House is again in need of some restorative work. The SJCHS is hoping to be able to address these issues during the summer months of 2015. We are soliciting match money for a grant application to the state Historical Fund. We need to raise 25% and we have already had one donation of $500 towards the project. If you are as amazed and impressed with the Old Hundred Boarding House as we are, please consider a donation to keep this amazing building from falling apart and tumbling down the mountain.

Please help us maintain the Old Hundred Boarding House with a DONATION to the San Juan County Historical Society.